Pet Owners -

FAQs: Bone Cancer in Dogs

Copyright © The Pet Oncologist 2019.

All Rights Reserved. Unauthorised distribution is prohibited.

What is osteosarcoma?

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive cancer arising from the bone. It is the most common primary bone cancer in dogs and typically occurs in the leg. This cancer predominately affects large dog breeds. Osteosarcoma is a serious cancer; however, with treatment, the vast majority of dogs can be significantly helped.

My vet took x-rays of my dog’s leg and saw a bone lesion. Does that mean that my dog has bone cancer?

Unfortunately, most dogs with a bone lesion will have osteosarcoma (>80%). However, other types of cancers are possible (such as fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, histiocytic sarcoma, and haemangiosarcoma). Less than 1% of bone lesions will be a benign lesion or infection (such as a fungal or bacterial infection).

What is the most common sign of bone cancer?

Most dogs with bone cancer in the leg will present with a limp and swelling in the bone; hence why it can be mistaken as a soft tissue injury or orthopaedic problem.

Will my dog be painful?

Cancer in the leg is very painful because small fractures and bleeding cause pressure on the sensitive nerve endings in the surface of the affected bone. Occasionally the fractures can be more severe, causing an actual break in the leg, which cannot heal (called a pathological fracture).

How do I check if my dog has osteosarcoma?

Diagnosis is usually confirmed with sampling the bone lesion by either cytology (fine needle aspirate samples) or biopsy (tissue sample).

Staging refers to how far cancer has grown and spread in the body. Staging is important to provide prognostic information on which to base decisions and identify unrelated problems that could affect treatment choices. Dogs are usually staged with chest x-rays, blood and urine tests.

The results of these tests will allow veterinarians to develop individualised treatment recommendations for your dog.

How do you treat dogs with osteosarcoma?

For the majority of dogs, amputation is the best treatment for cancer in the leg. Amputation will alleviate the pain produced by bone cancer, and also prevent the leg from being broken. Because amputation does not prevent the growth of cancer spread, a therapy that can reach the lungs and other body sites are required in order to avoid or delay the growth of these cancers. The most crucial advance and gold standard treatment for osteosarcoma in dogs is chemotherapy after amputation, which can slow the growth of cancer spread, dramatically improve life expectancy and in some cases, result in a cure.

The word ‘amputation’ sounds scary, and I do not think I want to go down this path. What now?

Although most dog owners initially do not like the idea of amputation, dogs (even large and giant breed dogs) respond to the surgery exceptionally well. Dogs can function well on three legs: they can go on long walks, play with family members and other dogs, swim and go up and downstairs. Most dog owners are pleasantly surprised to see how well their dogs adjust to the surgery. The pain associated with the procedure is minimal, and most dogs are up and walking the next day. Because dogs have no concept of their appearance, amputation is not associated with emotional or psychological difficulties for dogs. It is one of the most common and rewarding surgeries performed by veterinarians.

There is a website created by pet owners that have had amputation performed in their pets. This website may assist pet owners in deciding on whether amputation is an option for their pet. http://tripawds.com/. However, there are also other non-useful information on this website that veterinarians do not advocate. The videos and blogs on pet amputees may be helpful.

If you do not wish to proceed with amputation in your dog to treat cancer in the leg, other options include limb-sparing surgery (not all dogs are eligible), radiation therapy, Samarium radioactive iodine, bisphosphonates, and pain relief medications.

What if I have financial limitations?

If you have limited funds, it is still important to discuss all the available treatment options and associated costs with your veterinarian or a pet cancer specialist. At The Pet Oncologist, I work directly with your veterinarian to provide individualised treatment recommendations for each pet. I will review all the medical information submitted via the online submission form, and provide your veterinarian with a comprehensive written report within one to two business days. I will provide an interpretation of results, specific details about the cancer's biologic behaviour, prognosis, and multiple treatment options to cater to the individual needs of each pet and pet owner. I will also comment on whether further testing is required and address any specific questions or concerns. I can also provide chemotherapy protocols and client handouts to pet owners about the specific cancer and chemotherapy medications, to help pet owners make an informed decision. Unfortunately, due to legal reasons, I cannot provide online pet cancer advice directly to pet owners. However, your veterinarian will be able to discuss all these options with you before you consider treatment and can contact The Pet Oncologist with any questions or concerns.

Like and Follow on Facebook or Instagram!

Ella. A sweet 10-year-old female spayed Jack Russell Terrier diagnosed with aggressive bone cancer (osteosarcoma) in her left proximal humerus. Left untreated, most patients succumb to their disease within a few months. Amputation alone has a reported median (average) survival time of approximately 5 months. Amputation followed by chemotherapy has a reported median survival time of about 10 to 12 months, with approximately 20% of dogs alive more than 2 years later. Ella underwent amputation of her left forelimb, followed by chemotherapy. Unfortunately, after 10.5 months, Ella’s cancer spread to her lungs (i.e. pulmonary metastases). In general, in dogs with pulmonary metastases from osteosarcoma, the response to treatment is guarded with reported median survival times of approximately 2 months. Ella was treated with oral Palladia (toceranib) and survived for more than 5 years.

First image: X-ray of bone cancer before treatment, showing an aggressive bone cancer in the left proximal humerus (left forelimb)

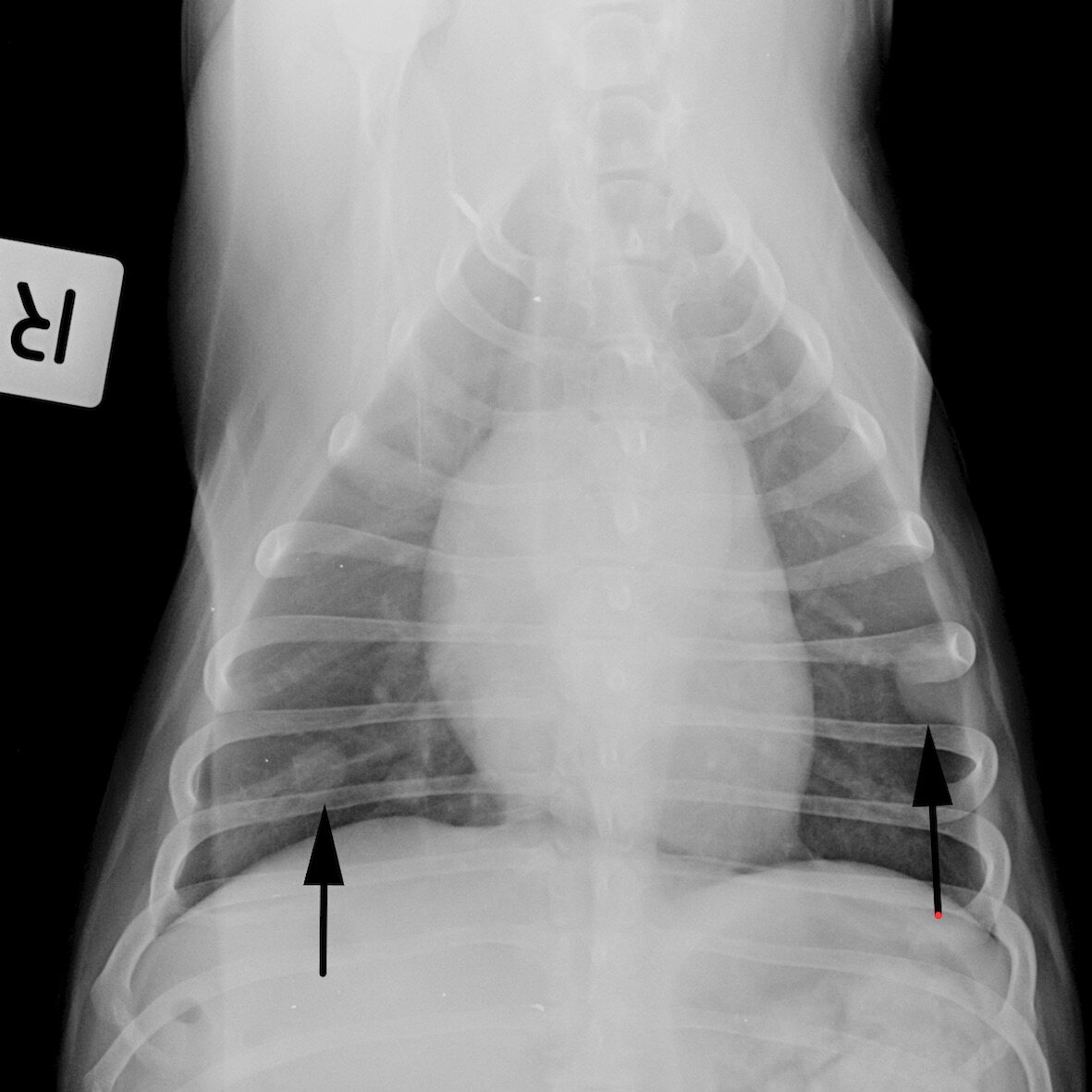

Second image: X-ray showing cancer spread to the lungs. Arrows indicate multiple nodules within the lung.

Third image: X-ray of the lungs after treatment, showing resolution of lung nodules.